When my children were small I thought it was terribly romantic to have an old-fashioned Christmas and leave a fresh orange in their stockings. I hoped they would feel the appreciation and gratitude of bygone years. It took me a while to figure it out, but the appreciation and gratitude finally came when I began putting chocolate oranges in each of their stockings. On the other hand, my children would never forgive me if I didn’t make our traditional French Chestnut Dressing.

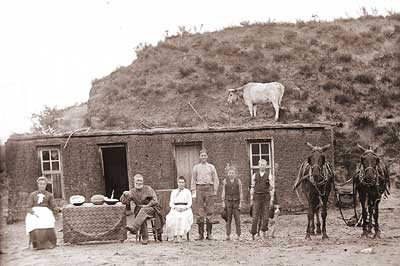

Pioneers brought with them recipes from their homeland and made them work with the ingredients they could find in their new adopted land. They also suffered deprivation when little food grew during the season. I think the children back then might have had a better understanding as they too suffered that deprivation. I ran across an article in an old Ensign that gives us an idea what the pioneers ate; adapting foods found and grown in the Salt Lake Valley from old family recipes, or creating something new with all that they had.

“Pioneer women who had to decide what few precious things to carry across the plains surely made one choice in common—their own individual collection of “receipts,” as recipes were then called. For them, these were reminders of a security left behind and a hope for the abundance of the future. In the interim, they simply did what they had to do to keep their families alive.

Many early memories of pioneer food concerned the frugality with which the Saints lived: “We lived on cornbread and molasses for the first winter.” “We could not get enough flour for bread … so we could only make it into a thin gruel which we called killy.” “Many times … lunch was dry bread … dipped in water and sprinkled with salt.” “These times we had nothing to waste; we had to make things last as long as we could.”

No doubt the “receipt” books were closed during these times, and efforts were given simply to finding food and making it go as far as possible. But slowly, even out of this deprivation, recipes grew. The pioneer women learned to use any small pieces of leftover meat and poultry with such vegetables as they might have on hand—carrots, potatoes, corn, turnips, onions—to make a pie smothered with Mormon gravy.

Thrift fritters were a combination of cold mashed potatoes and any other leftover vegetables and/or meat, onion for flavoring, a beaten egg, and seasonings, shaped into patties and browned well on both sides in hot drippings.

One Danish immigrant mother made “corn surprises” to brighten up the scanty diet of bread and molasses. To corn soup, made with ground dried corn, she added anything colorful or tasty that she could find: bits of parsley or wild greens, carrots, sweet peppers, chips of green string beans, chopped whites or yolks of hard-cooked eggs, or a little bit of rice.

By the time most of the immigrants were arriving, the critical food shortages were somewhat alleviated, with most families having access to milk and cream, butter and cheese, beef, lamb, pork, chicken, eggs, flour ground from their own wheat harvest, molasses and honey, and a little later, sugar.

Early diaries are filled with happy reminiscences of work and fun: salt-rising

bread mixed in mother’s “baking kettle” while traveling in the wagon, then baked over the campfire at night; bacon and sour-dough pancakes cooked over campfires; molasses taffy pulls made possible by generous drippings from the skimmings of molasses boilers; peach preserves cooked in the last of the molasses batch and stored in big barrels; fruits and vegetables dried for winter storage; buffalo pie and wild berries; raspberry and currant and gooseberry bushes planted near the house, yielding fruit quickly and easily.

Chickens were brought across the plains as early as 1847. A favorite among early recipes was velvet chicken soup, brought to the valley by an early English convert.

Velvet Chicken Soup

3 or 4 pounds chicken

3 quarts cold water

1 tablespoon salt

6 peppercorns (or 1/4 teaspoon white pepper)

1 small onion, chopped

2 tablespoons chopped celery

2 cups rich milk or cream

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1 tablespoon butter

Salt and pepper

2 eggs, well beaten

Thoroughly clean chicken and cut into pieces. Put in covered kettle with cold water and salt. Bring to boil quickly and simmer until chicken is tender. Remove chicken from stock and remove meat from bones (saving meat to use in croquettes, pie, etc.) Return bones to soup stock and add peppercorns (or white pepper), chopped onions, and chopped celery. Simmer together until a little more than a quart of stock remains in pan; strain, cool, and remove all fat. Add rich milk or cream, bring to a boil, and thicken with cornstarch that’s been mixed smooth with a little cold water. Add butter and season to taste. Beat eggs with a little cream. Pour 1 cup soup over egg mixture, stirring well, then pour egg-soup mixture back into soup, stirring constantly, and cook 2 minutes. Serve hot in soup dishes, adding bite-size croutons if desired.

Side Pork and Mormon Gravy

Mormon gravy, common fare among the early settlers and apparently a creation of necessity expressly for the times, is still hearty and nourishing for many of this generation who like to make it with ground beef or frizzled ham or bacon and serve it over baked potatoes.

8 thick slices side pork (or thick-cut bacon strips)

4 tablespoons meat drippings

3 tablespoons flour

2 cups milk

Salt, pepper, paprika

Cook meat on both sides in heavy frying pan until crisp. Remove from pan and keep warm. Measure fat and return desired amount to skillet. Add flour and brown slightly. Remove from heat and add milk, stirring well to blend. Return to heat and cook and stir until mixture is thick and smooth. Season to taste. Serve with side pork on potatoes, biscuits, cornbread, or even pancakes.

With the wild fruits—plums, cherries, grapes, gooseberries, currants—and the glorious fresh fruit cultivated so successfully from imported cuttings, the early pioneer women were soon making some of the delicacies that reminded them of “home.” Two of the favorites were Swiss apple-cherry pie, a recipe that came into the valley with a young Swiss convert who was famed for its making, and 101-year-old pastry, as good today as it was in the early days.

Swiss Apple-Cherry Pie

4 large cooking apples

6 tablespoons butter

2 1/2 cups pitted sour pie cherries, fresh or canned

1 cup sugar

2 tablespoons flour

2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon grated nutmeg

Make pastry for two-crust pie. Pare, core, and slice apples. Melt 2 tablespoons butter and brush on bottom of pastry shell. Arrange a layer of apples on bottom of pastry shell. Mix dry ingredients and sprinkle portion over layer of apples. Arrange layer of red cherries, then sprinkle with some of dry ingredients; then layer of apples and dry ingredients; layer of cherries and dry ingredients; and end with layer of apples. Top with dots of remaining butter. After top crust is added to pie, rub crust with cream or evaporated milk and sprinkle with mixture of 1/2 teaspoon sugar and 1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon. Bake at 425° F. for 30 to 40 minutes.

101-Year-Old Pastry

2 1/2 cups sifted flour

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 cup lard or shortening

1 egg, beaten

1 tablespoon vinegar

Cold water

Cut shortening into flour and salt. Beat egg lightly in a 1 1/2-cup measure; add vinegar and fill cup with cold water. Add just barely enough liquid to dry ingredients to hold dough together—about 4 tablespoons—reserving remaining liquid for next batch of pastry. Handle dough as little as possible. Roll out into pastry and use as desired. Makes two 9-inch pie shells.

Make a Pioneer dinner and feel the appreciation of a believing people who brought old security in a book of receipts and found new security in a Book of Mormon.

Information found in the Ensign, “A Melting Pot of Pioneer Recipes”, Winnifred C. Jardine, July 1972